A 2025 study from Maastricht University in the Netherlands examined how different break-taking methods affect learning among 94 university students during a two-hour self-study session. Participants were assigned to one of three groups and received different instructions for taking breaks:

- Self‑regulated (n = 25): Take breaks whenever and for as long as you want—i.e., at your own pace.

- Pomodoro (n = 36): A fixed cycle managed by a timer—study for 25 minutes, then take a 5‑minute break, and repeat.

- Flowtime (n = 33): Log your own start and end times, and take a break when your focus drops. Break length depends on the duration of the preceding work interval; for example, work ≤25 minutes → 5‑minute break; 25–50 minutes → 8‑minute break; ≥50 minutes → 10‑minute break. (A distinctive feature of Flowtime is that you decide when to break, but the length of the break scales automatically with the preceding work time.)

Each participant completed questionnaires before and after the study session and at every break, rating their motivation, fatigue, and productivity (how much progress they felt they were making). After the session, they also reported what percentage of planned tasks they completed (completion rate) and their sense of flow (being “in the zone”). The aim was to test which break‑taking technique most benefits subjective learning experience and task completion.

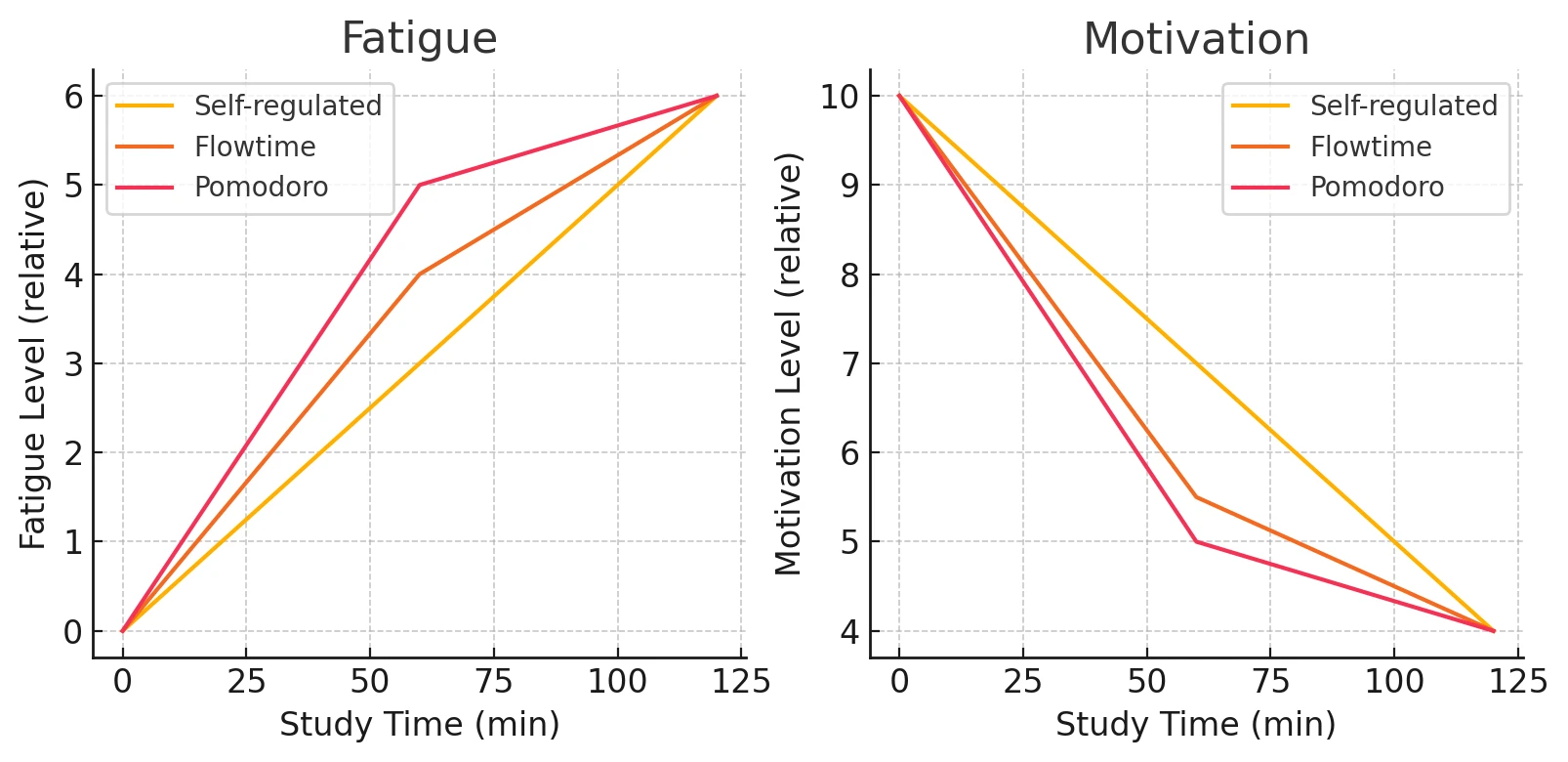

Changes Over Time in Fatigue and Motivation

Interestingly, the study showed that the temporal patterns of “fatigue” and “motivation” differed by break‑taking technique. Figure 1 illustrates the perceived changes in fatigue and motivation for each group.

Figure 1: Conceptual trajectories of fatigue (left) and motivation (right) over time by break‑taking technique. The vertical axis shows relative subjective levels (higher = higher motivation / stronger fatigue). The horizontal axis shows elapsed study time (0–120 minutes). Red = self‑regulated, orange = Flowtime, pink = Pomodoro.

From Figure 1, you can see that the Pomodoro group’s fatigue rose sharply early on (the pink line climbs quickly). In fact, students using Pomodoro tended to accumulate fatigue faster than the other groups.

The researchers speculate that because work is forcibly segmented every 25 minutes and break length is fixed at 5 minutes, some students may not have recovered enough during breaks. If you dive back into the next 25‑minute block without having fully recovered, fatigue may accumulate more readily.

By contrast, motivation declined more quickly in both the Pomodoro and Flowtime groups, while the decline was more gradual in the self‑regulated group. In Pomodoro and Flowtime, motivation tended to drop noticeably in the first half of the session, whereas self‑regulated learners (red line) maintained relatively high motivation for longer.

According to the research team, this may reflect stress from not being able to decide break length yourself. Pomodoro and Flowtime impose some rules on when and how long to break. For some people, this can create frustration—“I want a longer break but have to restart soon,” or “I wanted to break earlier”—and reduced autonomy may sap motivation. In contrast, self‑regulated learners take breaks at their discretion, likely reducing stress and slowing the decline in motivation.

The crucial point is that despite these differences in how things changed over time, by the end of the two‑hour session there were no significant differences in average fatigue or motivation across the groups. Even if some fatigued earlier or lost motivation sooner, by the latter half the self‑regulated group had also tired to a similar extent, and everyone ended up at roughly the same level.

Summary of Results: No Significant Differences in Productivity, Completion Rate, or Flow Experience

So, did the choice of break‑taking technique affect core learning outcomes? In short, no: whether students used Pomodoro, Flowtime, or self‑regulated breaks, there were no significant differences in the percentage of planned tasks completed (over two hours), self‑rated productivity, or degree of flow. On average, all groups completed roughly 70–80% of their planned tasks, and their sense of being in flow averaged about 4 on a 0–7 scale, i.e., virtually the same across groups. In other words, break style itself did not measurably sway short‑term learning outcomes.

However, “no difference in outcomes” does not mean “anything goes.” As noted, how you feel while studying (fatigue trajectory and motivation) does vary by technique. For example, Pomodoro’s frequent boundaries can help you refresh often, but the interruptions can also break flow more easily. Flowtime lets you get lost in the work but risks postponing breaks too long, leading to fatigue buildup. Self‑regulated breaks maximize freedom but come with self‑management challenges—you may under‑rest or, conversely, over‑rest.

In short, each method has pros and cons, and people differ in what fits them. The researchers likewise note that effects likely vary by individual factors such as personality and sense of self‑control. The next section maps which study styles or task types each method best suits.

Choosing Your Break Method: Which One Fits You? (Decision Guide)

The three break‑taking techniques tend to shine with different study styles and task types. Use this quick decision guide to map your tendencies:

-

Q1. Do you struggle to manage your own break timing? (e.g., you either push yourself nonstop or take meandering breaks)

→ Yes: If time management is hard for you, the Pomodoro Technique fits well. The short focus‑then‑break rhythm imposes structure, making it easier to keep moving without drifting. Especially for people who feel “it’s hard to get started,” the 25‑minute block lowers the barrier and works well against procrastination. Breaking big tasks into, say, four 25‑minute sets reduces the psychological load, making it suitable for exam prep and similar work.

→ No: If you can control your own break pace, proceed to Q2. -

Q2. Do you hate being interrupted once you’re locked in? (i.e., are you a “once I’m focused, don’t stop me” type?)

→ Yes: Flowtime is recommended for immersion‑oriented learners. Because breaks are flexible, you can stay with creative work or tough problems for a long stretch. Without an external timer breaking your rhythm, you can ride your own flow—great for idea generation or programming, where momentum matters. Just mind your self‑management: if you tend to forget to rest, be deliberate in choosing when to pause.

→ No: If interruptions don’t bother you, or you don’t typically maintain long focus stretches, a free‑timed, self‑regulated approach may suit you best. You don’t have to force a technique—simply rest when you feel tired and resume when you reach a natural stopping point. In this study, self‑regulated learners achieved comparable outcomes to the other methods and even held up well in motivation. If you either rest too little and end up exhausted or slack off too much, consider setting some minimal rules.

Try Flowtime: A Gentle Introduction to Pace‑Aligned Breaks

Finally, here’s how to put the lesser‑known Flowtime technique into practice. “Take breaks that match your own attention span.” The method is simple, but record‑keeping and adjustment are key to getting the most out of it. Follow the steps below for two weeks to discover your pace.

-

Learn the Flowtime basics: Don’t use a countdown timer; instead, take a break when your focus wanes. Use these starting heuristics for break length: ≤25 minutes of work → 5‑minute break; 25–50 minutes → 8‑minute break; 50–90 minutes → 10‑minute break; >90 minutes → 15‑minute break (and feel free to take longer if needed). Start by following this guide.

-

Keep records: Note your start time before you begin, and your end time when you switch to a break (a time‑tracking app is fine). Jot down brief reflections such as “how focused I felt” and “how tired I felt.”

-

Set small goals: If you tend to go for marathon sessions, don’t jump straight into a single 90‑minute push on a big task. Instead, set mini‑goals like “Do 30 pages of this problem set, then break.” This creates natural break points and lets you refresh before you’re wiped out.

-

Repeat for about a week: Practice Flowtime daily and accumulate records. You’ll begin to see patterns: “Around how long until my focus dips?” “What length of break actually restores me?” For example, you might discover “I’m most efficient if I pause around 45 minutes.” Patterns will differ by person.

-

Week 2: Optimize your pattern: Using week‑1 data, tweak break timing and length in week 2. If your focus typically dropped around 40 minutes, try stopping a bit earlier—say, around 35 minutes. If you sometimes last 60 minutes but other times only 30, adapt to that day’s energy level and task difficulty. If 5 minutes never feels sufficient, try 10 minutes or more. The key indicator is “Can I dive back in feeling refreshed?” (It’s far more efficient to continue with a fresh mind than to slog on while fatigued.)

-

Lock in your personal cycle: After two weeks, you should have a workable focus → break cycle that feels sustainable. Use it in future study sessions. For instance, if you find “about 50 minutes study + 10 minutes break” fits you, treat that as a default—your personal “timer.” Flowtime’s goal is to discover your optimal rhythm, not to bind you to Pomodoro’s 25/5. Ultimately, aim to establish your own pattern: X minutes study → Y minutes break.

In this article, we introduced the features and effects of three break‑taking techniques—self‑regulated, Pomodoro, and Flowtime—based on findings from a study of university students.

Each method has advantages and trade‑offs, but the essential task is to find what works for you. If this post made you think, “Maybe I’ll give it a try,” start with Flowtime.

It may feel like extra work at first, but with ongoing record‑keeping, your attention patterns will become clear. Knowing your best break timing is the first step toward more efficient, lower‑stress learning. Try it today and establish a study rhythm that truly fits you.

![Same Output, More Fatigue? The Pomodoro Technique’s “Unexpected Side Effect” [Tested with 94 University Students] のサムネイル](/blog/pomodoro-flowtime-self-regulated-study/pomodoro-flowtime-self_top.webp)