Stop Signs in the Flowtime Technique

Conclusion

Behaviors like your gaze drifting, slowed judgment, repeating the same mistakes, and tab wandering are stop signs. With the Flowtime Technique, it’s best to rest at the natural break.

What You’ll Learn in This Article

When you use the Flowtime Technique, start by observing stop signs in three categories: body, cognition, and behavior. Next, I’ll introduce a traffic-light model that lets you decide by signal whether to continue or rest. Then we’ll compare stopping too early versus working too long (overrunning) and sort out the downsides of each. After that, we’ll see how to vary your use of signs across three cases—creative work, templated routine work, and decision-heavy work. I also summarize a quick 90‑second check you can use when you’re unsure, and close by answering common questions that come up in practice.

Key Points at a Glance

| Theme | Signs / State | Immediate Action to Take | Tip to Remember |

|---|---|---|---|

| Three-Layer Signs | Dry eyes, slowed judgment, tab wandering, etc. | Micro‑break for body signs; step away for cognitive signs; stop for behavioral signs | These tend to chain body → cognitive → behavioral, so catch them early. |

| Traffic‑Light Model | Green = continue, Yellow = watch, Red = stop | Green: micro-adjust; Yellow: micro‑break; Red: rest immediately | Tuning up during Yellow reduces how often you drop into Red. |

| Deciding When to Stop | Too early vs. overrun | Take one breath at Yellow; stop immediately at Red | Measure your restart lag to learn your optimal line. |

| By Work Type | Creative / Routine / Decision‑heavy | Creative: brief step‑away; Routine: periodic rests; Decision: write it out, then rest | The meaning of each sign changes with the nature of the work. |

| 90‑Second Check | Can you write the next step? Three deep breaths? Try two minutes? | If it’s fuzzy, take a break; if you glide, continue | Gauge your subjective wobble before deciding. |

| Habit‑Building | Give signs vocabulary, externalize them, record them | Leave a one‑line memo and a color log | No tools needed—directing attention raises reproducibility. |

Break‑Time Signs You Can Read in Your Body, Head, and Behavior

The Flowtime Technique doesn’t chop work into fixed lengths; it assumes you rest when your concentration naturally breaks. For that, you need a mechanism to notice “Is now the time to rest?” by yourself.

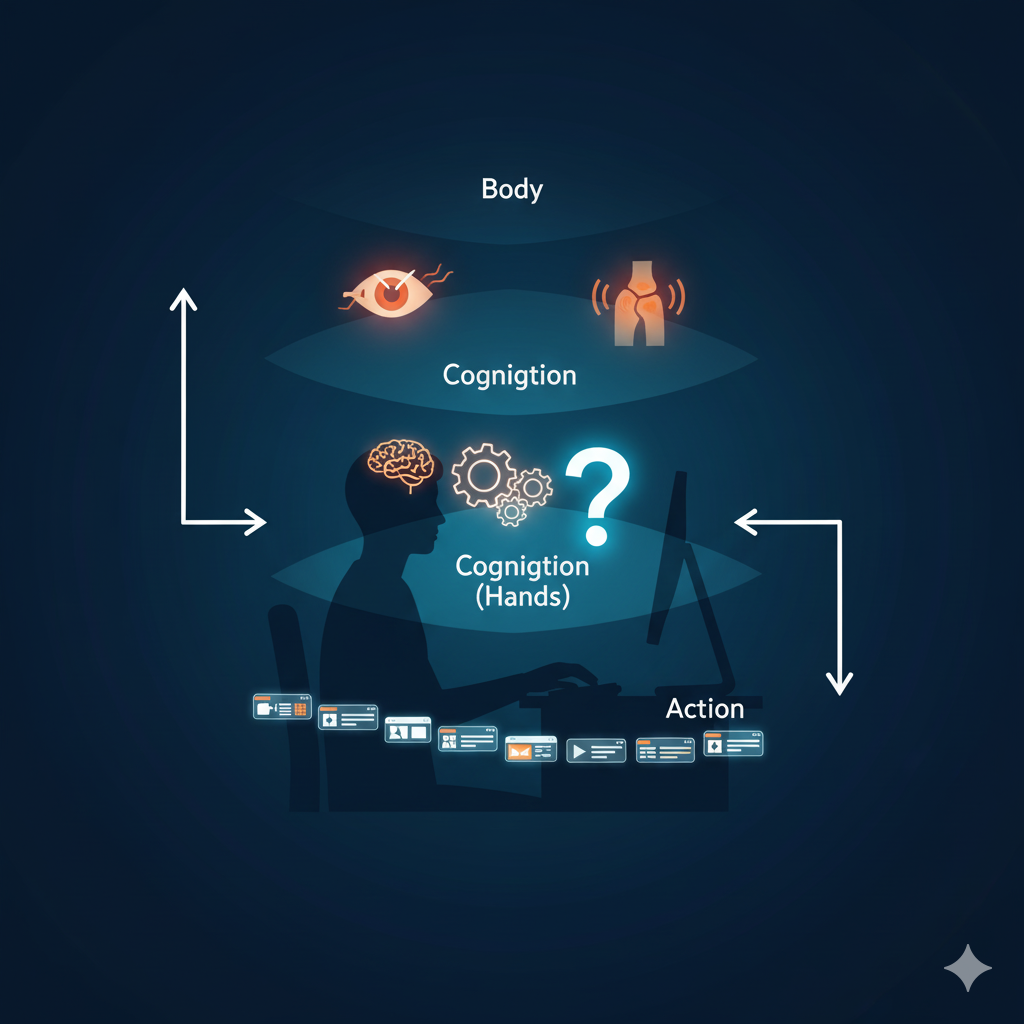

As the developer of FlowTime and a practitioner of the Flowtime Technique, I recommend viewing stop signs in three categories—body, cognition, and behavior.

There are two reasons. First, body signs come on quickly and serve as early‑stage fatigue signals, i.e., a yellow light. Second, cognitive and behavioral signs connect directly to work quality and drift, making clear the losses when you delay rest.

Body signs show up in your eyes, muscles, and automatic bodily functions—for example, dry eyes or changes in blinking, trouble focusing, slumped posture, repeatedly rubbing the same spot, and unwitting stretches or yawns.

This isn’t a medical diagnosis, but it’s a cue that your “body for working” is out of tune. If your gaze keeps freezing or slips off the screen, it usually means your attentional window is narrowing and your peripheral environment is drawing you in. Body signs recover quickly yet are easy to miss, so it’s vital to neither trivialize them nor overfear them.

Cognitive signs appear in functions like reading, recall, and judgment. More re‑reading, misreadings, repeating the same error, delayed decisions, and being unable to name the next task indicate you’re moving from yellow toward red.

When you’re focused, your mental “memory” aligns with the task and the flow before and after connects naturally. As fatigue builds, those connections fray; you ping‑pong within the same paragraph and logical snags stand out. This affects not just speed but also the stability of your finish.

Behavioral signs appear as actions that drift from the core task. You open and close barely related tabs aimlessly, scroll back and forth over the same spot, wander through settings without returning, follow notifications and can’t get back, or shift into file naming and folder tidying, deferring the main work. For me, opening social media is a glaring stop sign.

These are often misunderstood as “procrastination” or “escape,” but in reality they’re protective responses by your brain—natural avoidance behaviors when the balance of load and monotony breaks down. Once behavioral signs appear, fatigue is already present. If you keep going, you continue the task with impaired comprehension, so rework, omissions, and double handling shoot up.

The three sign types aren’t separate; they often surface with a time lag as body → cognitive → behavioral.

For example, a few minutes after dry eyes, your reading comprehension dips, and later tab wandering begins. That’s why catching body signs early is the most efficient cue to enter a break; if cognitive signs appear, step away briefly to reset your head; and when behavioral signs appear, rest without hesitation—that’s the baseline stance.

Color‑Based Rules for Switching: Green, Yellow, Red

To switch between progressing a task and resting without dithering, you need shareable cues. Map the three sign types to Green, Yellow, and Red.

Green means you have only light body signs while reading speed, decision speed, and task progress remain smoothly connected. Small adjustments—straighten your posture, shift your gaze slightly, slow your breathing—are enough to maintain focus. Resting arbitrarily here discards the momentum you’ve built and hurts efficiency.

Yellow is when cognitive signs stand out or body signs keep recurring. More re‑reading, repeated mistakes, and longer indecision are cues.

Recommended behavior in Yellow is a short break (micro‑break). Shift your gaze far away and practice breathing with longer exhales for about 30–90 seconds; if needed, stand briefly and stretch. A short detachment in Yellow gives your mind a fresh look to rebuild context and minimizes restart loss. Crucially, don’t mistake this short detachment for “running away.” Yellow is the moment to pause.

Red means behavioral signs are present and comprehension/judgment is stalling. Unstoppable tab wandering, being stuck on the same paragraph, drifting into file tidying or setting changes, and a hazy, foggy awareness are typical.

Forcing yourself to continue here makes typos and logical breakdowns snowball. Decide to stop and rest immediately. If you’ve been sitting, stand up, walk a little, hydrate, and look at daylight to switch your body. If necessary, write a one‑line note of your next action, then cut the task circuit decisively. Grinding in Red produces the worst time—only the feeling of “having worked” grows.

These three colors fluctuate over time. Some people stay in Green for long stretches; others cycle between Green and Yellow in short periods. What matters is observing your own flow and cultivating the courage to pause in Yellow and the habit to stop without hesitation in Red. In my experience, if you insert micro‑breaks correctly in Yellow, the number of times you enter Red clearly drops. The essence of the Flowtime Technique lies in the quality of your stopping points.

Stopping Too Soon? Grinding Too Long? How to Find the Sweet Spot to Stop a Task

Stopping either too late or too early is a problem.

Stopping too early sacrifices the heat of the run‑up just before concentration deepens. Every restart incurs an initial cost to re‑weave the flow (restart lag), and your day’s rhythm becomes jagged.

As a result, your day’s net focus time shrinks, and the unity and tone of the output get uneven. Conversely, overruns add fatigue debt, which comes due as quality deterioration in the following days. Near the finish, mistakes slip in, you overlook rough logic, or add low‑value decorations; what feels like “one more step” invites “three steps of rework.”

The key is to separate short‑term satisfaction from long‑term results. If you lean on short‑term achievement, overruns seem convenient. But on long‑term average output, proper stopping always wins. Taking a deliberate breath in Yellow is a strategic investment: “If I rest now, I’ll return with a notch‑higher perspective.” By contrast, pushing on in Red snowballs error rates and fix time. The courage to stop and the grit to continue can coexist. You can keep going because you stop.

You often hear numbers about “how long it takes to get back after an interruption,” but applying those to yourself as‑is is risky. Recovery time varies widely by task type, familiarity, note‑taking, and the quality of the break. That’s why it’s essential to measure your own restart lag. A simple method: note the time you resume and record either the felt time until your groove returns or the time to your first meaningful milestone. Do it for about three days and you’ll see the trend.

The Flowtime Technique is both tuning your senses and a measurement discipline.

Switching Guide by Work Type

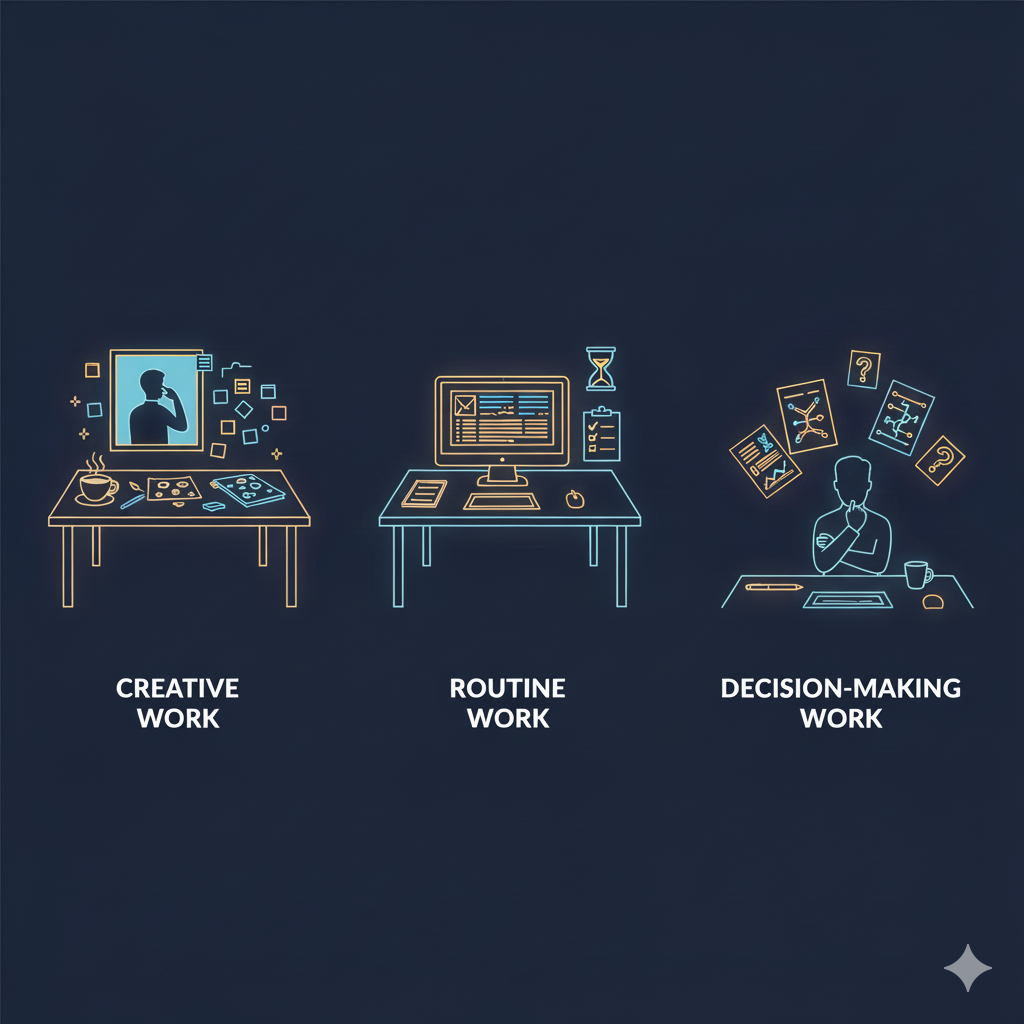

I believe your perception of stop signs should change with the type of work.

For creative work (ideation, writing, design, research), often simply stepping away briefly on Yellow and returning brings ideas back. Creativity runs on small back‑and‑forths between expanding and consolidating.

At Yellow, cast your gaze far, breathe longer, and add just one off‑angle stimulus. When you return, restart from your opening sentence and sketch metaphors or structure by hand. By creating a slight change in angle, new associations emerge. The big NG here is wandering into deep information forays while Yellow—link surfing and getting lost in organizing materials cool the creative heat. The golden rule: step away lightly, return quickly, and write one sentence.

For routine work (reviews, conversions, data shaping, repetitive tasks), it’s easier to preserve quality by resting briefly at Yellow rather than waiting for Red. Monotony erodes motivation and invites repeat errors. Merely changing viewing distance and resetting posture at fixed intervals raises your error‑detection. Here, the number of breaks matters. For example, after about forty minutes, when Yellow starts peeking in, insert a 90‑second refresh. In the Flowtime Technique, there’s a method that allocates 20% of work time to breaks, automatically calculating break length to help you sustain the next focus.

After returning from a break, open your checklist. Don’t just plow on—first declare “Where am I likely to slip now?” and give a role to your attention. In routine work, accuracy beats speed.

For decision‑heavy work (design choices, prioritization, hiring decisions), before your wavering stretches out, make it a rule to write things out, then break.

Write options, evaluation axes, constraints, risks, and hypotheses in short lines to make what you’re thinking visible. If you sense Yellow, step away to widen your field.

Exposure to breeze, light, and far views often softens the state of being locked onto one answer and restores your feel for grasping the whole. Beware the easy thought, “The deadline is close, so I won’t stop.” There are moments when you need the courage not to stop, but only when the Yellow wave is shallow. In most cases, a short stop is better.

A Simple 90‑Second Protocol When You’re Unsure

If you’re torn about stopping or continuing, run a quick 90‑second check. The steps are simple. First, try to write the “very next thing” for your current task in one sentence.

If you can’t, that’s a sign of mental fog. Next, take three slow deep breaths and throw your gaze far. If this settles your bodily discomfort, you might return to Green.

Finally, return to the same spot and work for just two minutes as a warm‑up. If your sense of focus doesn’t return and the one‑liner you wrote remains fuzzy, switch to Stop → Break. Conversely, if your hands start moving smoothly within two minutes, you’re back in Green. The purpose of the 90‑second check is to capture wavering subjectivity with a tiny measurement—turn dithering time into decision time.

The 90‑second check is neither an excuse to flee nor an excuse to endure. You simply switch quietly according to the measured response. Writing things out helps here as well.

Summarizing the next task or subtask in a single sentence re‑evokes the goal and tells you where to return. If you can’t write it, what you’re reacting to is blurred. So you stop. Stopping is not losing. It’s a professional move to protect the circuit.

Regardless of how long I’ve been focused, when a natural breakpoint in the task arrives and I feel I want a quick rest, I press the Break button and start a break. It’s not that short time means you can’t rest; rather, by marking a boundary and continuing to think about the task during the break, I often come back with better ideas and improvements.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why start from body signs?

Because the body logs the earliest signals. Changes in blinking, a fleeing gaze, shallow breathing, and muscle stiffness often precede cognitive disruption. Body signs can be stabilized at low cost, so if you face them early you can prevent the spread into cognitive and behavioral signs.

Sometimes simply resetting your gaze or standing up is enough to restore reading speed. Because you get a big effect for a small intervention, you start by watching for bodily anomalies. This is the opposite of “gutting it out” and a smart choice to engineer the process for energy efficiency.

How do I distinguish drowsiness from boredom?

Drowsiness is chiefly the body trying to sleep, showing up as heavier blinks, trouble focusing, and a sinking torso. Boredom is a breakdown in motivation/stimulus balance, surfacing as behavioral drift like tab wandering, unnecessary setting tweaks, and escaping into decorative edits.

Drowsiness recovers with a short nap or strong stimulation; boredom responds to reframing the work’s meaning or changing constraints. If, in the 90‑second check, you can’t write the next task/subtask but your bodily sense is intact, it’s likely boredom. Conversely, if your body is heavy and your field of view narrows yet you still see what you should do, it’s more drowsiness. Once you can tell them apart, your response can change—use a full stop for drowsiness and a light switch‑up for boredom.

Right before a deadline, is it okay not to stop?

Deadline‑adjacent decisions are risk management. Choosing not to stop carries risks of quality degradation, more errors, and ballooning rework. Choosing to stop carries the risk of time spent. The rule of thumb is simple: If it’s Red, stop. Continuing in Red only adds noise. If it’s Yellow, insert “write it out, then a short break,” then return and reset priorities. The closer the deadline, the more vital it is to have short‑stop techniques. Use 30–90‑second, high‑quality breaks to reset gaze, breathing, and posture, then return with a one‑line next step. Meeting deadlines isn’t about sheer willpower; it’s about maintaining the circuit. The courage to stop is your ally in meeting due dates.

Three Habits You Can Start Today

First, give your signs names. Express your body/cognitive/behavioral signs in concrete words that fit you—“heavy gaze,” “can’t read the context,” “cursor lost,” metaphors are fine. Putting them into words speeds up noticing. I like using gaming lingo such as “my brain is starting to jam” or “I’m getting sluggish.”

Second, make writing things out part of your routine. At the start, write the goal in one sentence; during the task, write the next task in one sentence; and when stopping, leave a one‑line re‑entry note. These three sentences become bridges of focus. Third, record Green/Yellow/Red for just one week. At day’s end, jot a few lines on each session’s start, end, color, why you stopped, and restart lag. That alone reveals your rhythm.

These habits don’t need special tools. What you need is how you direct attention. Concentration isn’t something you grab once and keep—it’s something you relaunch repeatedly. If you manage your stop signs well, they become a wellspring of productivity. Stopping supports continuing. Whether the Flowtime Technique matures for you hinges on this.

Summary: The Power to Stop Becomes the Power to Continue

Stop signs aren’t alarms that break concentration—they’re notices that protect it. Observe signs across body, cognition, and behavior. If Green, continue; if Yellow, tune up briefly; if Red, stop without hesitation. Stopping too early crushes your run‑up; overrunning leaves a cost to pay tomorrow.

In creative work, stepping away on Yellow and returning sparks insight; in routine work, Yellow protects quality; and in decision‑heavy work, write it out, then a short break restores your feel for the whole. When in doubt, use the 90‑second check to measure how you feel and then decide. The courage to stop generates the power to continue. This is the pro’s stopping point in the Flowtime Technique.

You can find How to Resume with the Flowtime Technique here. The Guide to Choosing Tasks Suited for the Flowtime Technique is here. Please head here for The Overview of the Flowtime Technique.

If you haven’t started with the Flowtime Technique yet, take a look at the Complete Guide to the Flowtime Technique.

References

Ariga, A., & Lleras, A. (2011). Brief and rare mental breaks keep you focused: Deactivation and reactivation of task goals preempt vigilance decrements. Cognition, 118(3), 439–443.

Monsell, S. (2003). Task switching. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 7(3), 134–140.

Smallwood, J., & Schooler, J. W. (2015). The Science of Mind Wandering: Empirically Navigating the Stream of Consciousness. Annual Review of Psychology, 66, 487–518.

Boksem, M. A. S., & Tops, M. (2008). Mental fatigue: Costs and mechanisms. Brain Research Reviews, 59(1), 125–139.

Sheppard, A. L., & Wolffsohn, J. S. (2018). Digital eye strain: prevalence, measurement and amelioration. Contact Lens & Anterior Eye, 41(1), 99–106.

Altmann, E. M., & Trafton, J. G. (2002). Memory for goals: An activation-based model of the Zeigarnik effect. Psychological Science, 13(2), 171–179.

Sio, U. N., & Ormerod, T. C. (2009). Does incubation enhance problem solving? A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 135(1), 94–120.

Pashler, H. (1994). Dual-task interference in simple tasks: Data and theory. Psychological Bulletin, 116(2), 220–244.

Lim, J., & Dinges, D. F. (2010). A meta-analysis of the impact of short-term sleep deprivation on cognitive variables. Psychological Bulletin, 136(3), 375–389.

Danziger, S., Levav, J., & Avnaim-Pesso, L. (2011). Extraneous factors in judicial decisions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(17), 6889–6892.