How to Choose Tasks for Flowtime

Conclusion

Flowtime is effective for work that is uncertain, time‑consuming, and important. Tasks that are short with predetermined steps or require matching others’ schedules are more efficient with different methods.

The Flowtime Technique is a simple approach that switches between work and rest in tune with your own waves of concentration. You rely on your internal sense rather than a timer. This mindset strongly influences task selection. Flowtime is not suitable for every kind of work, and forcing it onto ill‑suited tasks can actually lower efficiency. In my work helping organizations improve operations, I have seen this difference many times. This article explains how to identify tasks that fit Flowtime and how to handle borderline cases.

Here’s the structure of the article. First, we’ll introduce a way to assess tasks along three axes—“uncertainty,” “length,” and “importance.” Next, we’ll provide concrete examples of tasks that do and do not fit. Then we’ll offer tips for making ambiguous tasks easier to move forward, along with field‑specific points for development, writing, learning, and research. After that, we’ll cover environment setup, structuring your day, team usage, and frequently asked questions. By the end, you should feel confident deciding “I’ll use the Flowtime Technique for this task” versus “I’ll use another method for that.”

Quick Reference of Key Points

| Theme | Key Points | Examples / How to Check |

|---|---|---|

| Tasks where Flowtime is effective | Choose work that is uncertain, time‑consuming, and important. Use Flowtime to protect tasks whose output degrades when interrupted. | Designing a new feature, drafting a complex piece of writing, revisiting hypotheses, etc. |

| Three axes to judge fit | Roughly rate uncertainty, length, and importance as low/medium/high. If two or more are high, it’s a candidate. | Ask yourself: “Will I need more than 30 minutes of continuous thinking?” “Will interruption lower quality?” |

| How to structure borderline tasks | Split by deliverable and separate research from production. Allow sessions that are prep‑only Flowtime. | Treat “write the introduction,” “build a prototype,” or “organize source materials” as one session’s deliverable. |

| Tips for ongoing use | Maintain start/end rituals and log your focus level to sustain concentration. Separate response time and production time. | Ritual example: turn off notifications and record the task name → at the end, jot a one‑line progress note. If focus is below 50%, revisit your setup. |

| Rolling it out to a team | Share no‑interruption windows and a logging format to balance focus with collaboration. | Declare morning focus hours, batch review replies into two windows per day, and include “next action” in logs. |

Understand the Fit Between Flowtime and Tasks

The Flowtime Technique values continuing while you’re riding a wave of focus and resting when that wave recedes. The more a task benefits from pushing through to a natural stopping point, the more Flowtime improves both quality and speed. Conversely, tasks with fixed steps that end in a few minutes are better handled in quick bursts using other methods. And for time‑fixed work like meetings, Flowtime’s flexibility is hard to leverage. That’s why it’s crucial to identify the nature of each task.

Judge Fit Across Three Perspectives

To assess suitability, check “uncertainty,” “length,” and “importance,” in that order. Here’s a plain‑language explanation of each.

Uncertainty is how much you can’t know until you actually start. Designing a new feature, writing on a first‑time topic, or revising research hypotheses are high‑uncertainty. Proofreading a known text for typos or entering numbers into a template are low‑uncertainty. The higher the uncertainty, the easier it is to lose your train of thought when interrupted—so Flowtime’s ability to protect concentration is especially useful.

Length indicates how much continuous focus time you need in one sitting. It’s not the calendar duration, but the uninterrupted stretch required to feel traction. Designing a system or drafting a difficult section often gains momentum after 30–60 minutes. In contrast, 5‑minute checks or brief messages are better handled by switching quickly than by gearing up for a long stretch. As a rule of thumb for continuous focus time, use “Does it exceed 30 minutes?” as a criterion.

Importance is how much the outcome affects others. Decisions that impact many people, judgments that greatly influence quality, or validations that determine whether a release can proceed are high‑importance. Advancing high‑importance work with shallow focus often invites rework later. For such work, it’s worth securing protected, uninterrupted blocks.

Putting the three together, tasks that are high‑uncertainty, long, and high‑importance are ideal for the Flowtime Technique. Conversely, low‑uncertainty, short, low‑importance tasks should be processed quickly with another method. When in doubt, say out loud: uncertainty = low/medium/high; length = short/medium/long; importance = small/medium/large. If two or more are high/long/large, treat it as a Flowtime candidate.

Work Suited to Flowtime—and Work That Isn’t

Flowtime pairs well with ideation, complex implementation, searching for solutions to hard problems, and long‑form writing. Here, the time spent thinking is what creates value. If a notification drops in and breaks your chain of thought, it takes time to descend back to a deep level of focus. For work that gains momentum as the context of thought persists, protecting it with Flowtime has outsized benefits.

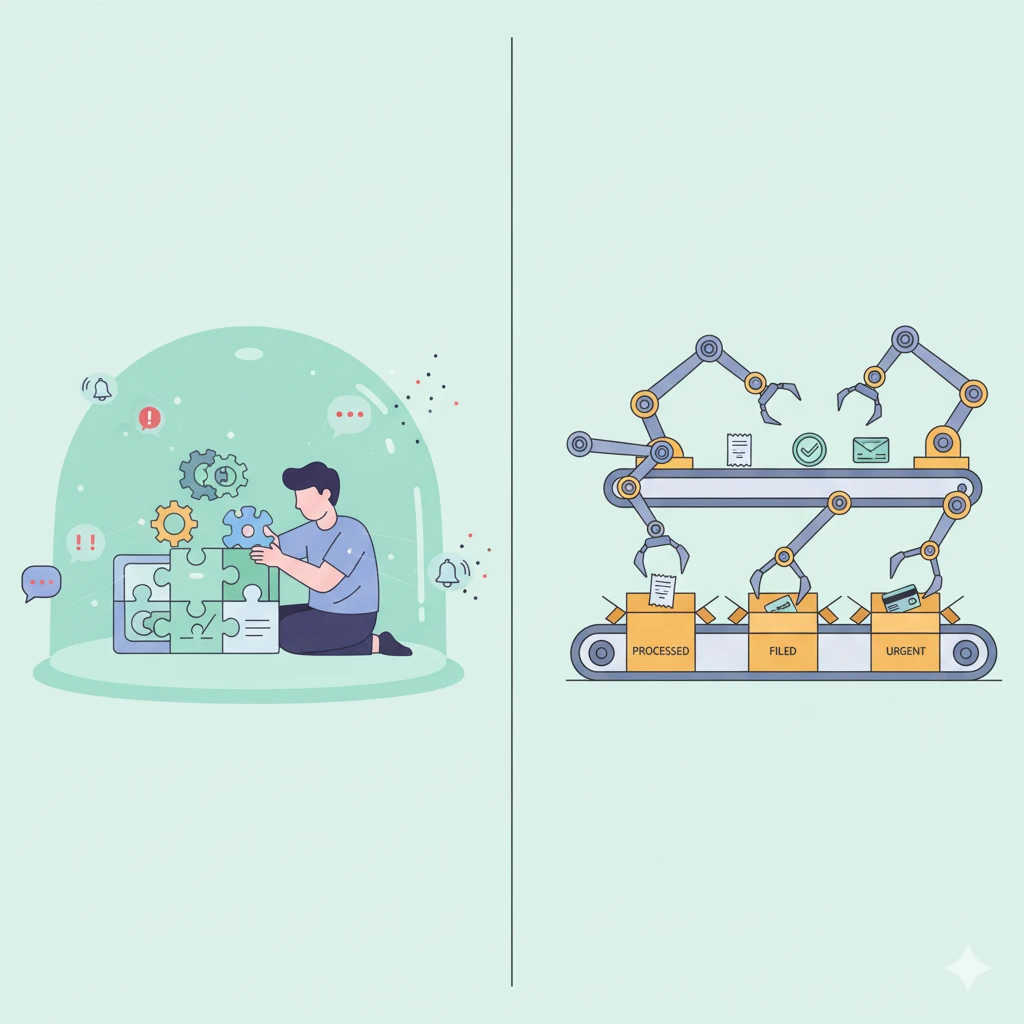

Flowtime is not a good fit for email triage, minute‑long chores, or messages where you’re awaiting a reply. Blocking off 45 minutes to attach expense receipts and send them is counterproductive. Short tasks are easier on your brain when completed in small batches; your daily rhythm stays smoother too. And work that won’t move without someone else’s review or approval can’t progress on your focus alone, so Flowtime’s flexibility is harder to exploit.

One point not to misunderstand: “not suited to Flowtime” does not mean “low value.” The lower a task’s value, the more important it is to process it quickly in batches. Simple tasks are precisely where batching, automation, and templating can raise output per hour. By reserving focused time for high‑value, uncertain, and time‑consuming tasks, you maximize overall results.

Tips for Moving Forward on Borderline Tasks

On the ground, you’ll often encounter tasks where you’re unsure whether to apply Flowtime. The main reasons are that the task is defined too broadly or too narrowly. Here are two tips to make such tasks easier to start.

First, split the work into visible deliverables. Use units like “write the problem‑posing introduction,” “build the skeleton of the comparison table,” or “summarize the key points for the conclusion.” When you break it down to the smallest unit you could hand to a stakeholder, it becomes clear what you’ll finish in one Flowtime session. When the boundaries of the work align with the boundaries of the deliverable, you’ll find a natural moment to stop and an easier transition into a break.

Second, separate research from production. Mixing the two invites stalls. When implementing a new technology, use the first session to build only the smallest working experiment, and the next to translate it into real code. In writing, split it into: gather materials → craft the outline → draft the body. Research is drawing the map; production is walking the route. If you try to do both at once, you end up redrawing the map while walking—and both slow down. Flowtime is most effective when this separation is clear.

Small tweaks that lower the barrier to entry also help. It’s fine if your first session is a prep‑only Flowtime—tidy the desk, open materials and editor, and list what you won’t do today. Creating a setup where future‑you can start immediately is a deliverable in itself. Giving yourself permission to end with preparation alone gets the task moving and makes it easier to ride the Flowtime wave in subsequent sessions.

Field‑Specific Tips

From here, we’ll look at how to use Flowtime across four areas: development, writing, learning, and research. Across all fields, the common attitude is to protect the continuity of thought that creates value.

In development, Flowtime primarily targets design, exploratory implementation, and diagnosing tricky bugs. When shaping a new feature’s data model, you juggle multiple cases while holding assumptions in your head. A notification at that moment forces you to rebuild mental context. Design and exploration accelerate in 30–90 minute blocks, so protect them with Flowtime. Save light tasks like code formatting or log tidying for warm‑ups and cool‑downs to keep your rhythm. Even reserving a Flowtime block just to enumerate review angles before you request a review can reduce back‑and‑forth and speed the whole process.

Writing is especially well‑suited to Flowtime. Work that speeds up as the words start to connect—drafting an outline, structuring a complex argument, crafting a compelling introduction—improves markedly when you ride Flowtime’s wave. Begin by skimming your sources and writing one sentence that states “what change you want to create in the reader.” The clearer the intended change, the easier it is to cut extraneous information, and the deeper your focus becomes. Then finish the body one section at a time as deliverables, and batch light tasks like typo checks and figure captions at the end.

For learning, use Flowtime for written practice and for checking whether you can explain concepts to someone else. Simply staring at important definitions rarely generates a focus wave. Learning that involves your own hands moving is exactly the kind of continuity you want to protect with Flowtime. Start by writing a short learning target such as “I can explain in my own words how to find the vertex of a quadratic function.” Then solve problems, note what you didn’t understand, and finally reflect on your grasp. This helps the material stick.

In research, apply Flowtime to tasks requiring sustained focus such as understanding a paper’s structure, organizing data, and recombining hypotheses. Reading prior work is costly to resume when interrupted because recalling context takes time. Secure a solid Flowtime block, and end by noting “the next analysis to try” and “sources to check,” which smooths your restart.

When reviewing your Flowtime logs, quantify “how focused you were” to generate insights. Try recording a focus ratio: time spent truly focused divided by your total Flowtime duration. If days below 50% continue, it’s a sign that task selection or environment needs adjustment. If days above 70% increase, your selection criteria likely fit you well. There’s no need to obsess over the numbers; tracking them calmly as a learning indicator is enough.

Build an Environment That Protects Focus

Flowtime’s value increases with the right environment. Small start and end rituals improve how you ramp up and switch gears. A start ritual can be as simple as tidying your desk, turning off notifications, and writing the task name on paper. An end ritual can be as simple as writing a one‑line note on what moved and jotting down the next action. When “what to do next” is visible, your resistance to restarting drops dramatically.

Countermeasures against interruptions are crucial too. Follow the simple principle of not mixing time for responses with time for production. In response time, batch replies to messages, push approvals, and reduce items stuck waiting on others. In production time, turn notifications off and immerse yourself in your own context. Splitting these within your day makes the continuity that Flowtime protects far less fragile. If possible, tell people, “I’m focused during these hours, so my replies may be slow.” Declaring it also turns a promise to yourself into something visible.

Three Checks Before a Flowtime Session

Before applying Flowtime to a task, ask yourself three questions. First: “Will breaking the continuity of thought degrade the outcome?” If yes, it’s a Flowtime candidate. Second: “Does this task have a natural stopping point that’s easy to find?” The easier it is, the easier it is to decide when to rest. Third: “Will I have a deliverable at the end that I can hand to someone?” If yes, you’ll feel progress and sustain motivation. If two or more answers are “yes,” apply Flowtime without hesitation.

Why Flowtime Works—A Clear Rationale

Flowtime is effective because it aligns with how concentration works. Deep focus emerges when challenge is appropriate and feedback is clear. If it’s too hard, you feel anxious; too easy, you feel bored. Because Flowtime lets you define the boundaries by feel, it’s easier to maintain appropriate challenge and feedback. Also, every task switch incurs time to recall goals and reboot rules. Because Flowtime switches only when necessary, it reduces that waste. As a result, the context of thought persists longer and memory consolidation improves. Deliberately creating cohesive blocks of focus elevates the quality of learning and creation—Flowtime supports this simple truth.

An Example of a Flowtime‑Centric Day

Here’s an example of structuring a day around Flowtime. In the morning, run a short Flowtime for preparation to decide “what not to do today.” Deciding what not to do is your first investment in protecting focus. Then, during the high‑energy morning hours, tackle two of your most important, time‑consuming tasks. Before lunch, carve out a short response window to batch‑reply to messages and approvals. In the afternoon, run lighter Flowtime blocks for editing prose or fine‑tuning designs, and in the evening add another response window to clear external blockers. Finally, write a few lines on what you learned and note tomorrow’s first action—this makes the next day’s ramp‑up smoother.

Of course, this is only an example. Learn from your logs when you focus best. Some people peak in the morning; others in the late afternoon. Use Flowtime as a mirror to understand your rhythm and fold those findings into your daily structure.

Tips for Team Adoption

Individual productivity needs to combine with team velocity. Flowtime is a personal method, but paired with team rules it can accelerate collaboration. For example, designate a one‑hour no‑interruption window for the whole team in the morning, or batch replies to reviews twice per day. The fewer interruptions, the more each person’s Flowtime can shine—and deadlines and quality improve.

It also helps to distribute a list of discussion points and a decisions template before meetings. Meetings get shorter, and the post‑meeting re‑warm‑up time shrinks as well. Sharing a Flowtime log template within the team is recommended too. By writing just five things—“start, end, content, blockers, next action”—you make it clear when and how to ask for help, which makes support easier.

Common Pitfalls

Here are three common Flowtime pitfalls. The first is over‑applying it. You may want to put everything into Flowtime, but if you include short response tasks, your day loses agility. The second is over‑measuring. Logging matters, but if you obsess over minute‑level precision, recording becomes the goal. Coarse granularity sufficient to generate learning is enough. The third is over‑isolating. In protecting focus, you may neglect others’ requests. Avoid this skew by clearly scheduling response windows. With balance, individual focus and team progress can coexist.

FAQ

Q. Should I include work that takes 10–15 minutes in a Flowtime session?

A. At that length, batching is more practical, and the Pomodoro Technique is recommended. However, if the work includes heavy judgment, insert a mini‑Flowtime beforehand to write three lines of evaluation criteria. Even a short session makes decisions easier.

Q. The task is too big to start. How should I split it?

A. Split by deliverable and separate research from production. Give yourself permission to end the first session with preparation only, creating a state where future‑you can launch immediately. Preparation is legitimate progress—and once the task is moving, it’s easier to ride Flowtime.

Q. Can I use Flowtime in a role with many meetings and handoffs?

A. Meetings and reviews themselves are time‑fixed and therefore not a great match for Flowtime, but protecting the before‑and‑after preparation and consolidation with Flowtime is effective. If the team shares a rule to separate response time and production time, individuals will also find it easier to secure Flowtime.

Wrap‑Up: Choose on Three Axes; Improve with Preparation and Logging

Flowtime delivers its greatest benefits on tasks that are uncertain, time‑consuming, and important. Don’t force in tasks that don’t fit. For tasks you’re unsure about, split by deliverable and separate research from production. Reduce switch friction with start/end rituals, and learn your rhythm from logs and apply it to the next day. Once this cycle spins, your daily productivity rises quietly but steadily.

Rather than chasing perfection, pick just one task that feels suited to Flowtime, decide the very next step, and start. Once you catch a wave of focus even once, your body will remember. That feeling invites the next round of focus. Respect your rhythm and protect the continuity that creates value—this is how you make Flowtime your ally.

For How to Stop Flowtime Technique, click here.

For How to Restart Flowtime Technique, click here.

For the Overall Picture of Flowtime Technique, please go here.

If you have never started Flowtime Technique before, be sure to check out the Complete Guide to Flowtime Technique.

References

How to use the flowtime technique to boost your productivity — Zapier

Flowtime Technique: An Alternative to Pomodoro — UBC Learning Commons

The Flowtime Technique: A Complete Guide — Timely

The Cost of Interrupted Work: More Speed and Stress — Gloria Mark et al., CHI 2008 (PDF)

Multitasking: Switching Costs — American Psychological Association

Executive Control of Cognitive Processes in Task Switching — Rubinstein, Meyer, Evans (2001) (APA/PDF)

Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience — Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (Book)

The Pomodoro Technique — Francesco Cirillo (Official)

Maker's Schedule, Manager's Schedule — Paul Graham (Essay)

Deep Work — Cal Newport (Book/Publisher page)