Restart Cues for the Flowtime Technique

Conclusion

Moving in the order of 1-sentence note → 3 deep breaths → 2-minute warm-up sharply reduces the “hard to get back into it” feeling after an interruption. Right after restarting, don’t aim for perfection—use a cue that says “moving forward a little is enough” to rebuild momentum.

What You’ll Learn in This Article

- Why task restarts often feel difficult

- How to decide the very next step in a single sentence

- How to do the three deep breaths and the two-minute warm-up

- Practical responses tailored to different reasons for interruption

- Checkpoints for when you’re stuck and answers to common questions

Quick Reference of Key Points

| Theme | Core Message | Concrete Actions & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Why restarting is hard | A break in flow, residue from other tasks, and perfectionism interact to raise the hurdle to restart. | Keep the causes in mind as a set and switch to small restart cues the moment you notice them. |

| Step 1: Restart note | Summarize your next move in one sentence of about 20–40 characters to clarify the entry point for moving your hands. | Write with “object + verb + deliverable + necessary quantity or time,” then skip revising and move straight to Step 2. |

| Step 2: 3 deep breaths | Regulate breathing with inhale 4 counts, lightly hold 1, exhale 6, letting go of tension and evaluative thinking. | Plant your feet on the floor and repeat the same rhythm three times (up to six if needed). |

| Step 3: 2-minute warm-up | Use light, pre‑work actions to recover context and finger feel before the main work. | For writing: read aloud or tidy headings. For code: run a test or refine variable names. Keep it to two minutes. |

| Hints by reason for interruption | Split responses into three patterns: external factors, your state, and process/plan gaps. | External asks and worries go to a note; sleepiness → move your body; planning gaps → checklists to reduce dithering. |

| Checks when you still can’t return | Review the granularity of the restart note, the order of breathing and warm‑up, and whether you noted your feelings. | Split an oversized note; restore any missing steps; put unease into words. |

| FAQ essentials | Combining with other methods, long gaps, team sharing, learning use, and habit targets are the key points. | Use with Pomodoro; for half‑day gaps do 2 min × 3 sets; share templates; speak aloud when studying; aim for two weeks to settle. |

Why Does Restarting a Task Feel So Hard?

Failing to restart a task isn’t about weak willpower. Three common causes are:

- Forgetting the flow — You can’t recall how far you got, and your hands stall.

- Lingering residue from what you were just doing — Your gaze drifts toward that other work.

- Fear of not doing it well — As soon as you restart, you want to score yourself, and the first step feels heavy.

These three reinforce each other. The more you forget the flow, the stronger the anxiety; the stronger the anxiety, the more you tense up with “I must do it perfectly from the start.” Sudden interruptions from notifications or conversations also tighten the body and shallow your breathing, making fine work harder. That’s why it’s vital to stack small cues and ease back in.

Step 1: Decide the Next Step with a Single Note

First, summarize your very next move in a one‑sentence note of about 20–40 characters. In this article, we call this sentence a “restart note.”

- A handy shape is “object + verb + deliverable + quantity or time if needed.”

- Examples: “Write the report’s conclusion in three lines.” “Create two headings for the bug reproduction steps.” “Copy two official examples into the notebook.”

A restart note is for your eyes only, so reuse the exact words you used last time. Using your usual terms and variable names helps your mind fetch information from the same mental shelf. The note can live in an app or on paper, but place it where it sits alongside your work screen so you can glance at it. Instead of “I will ~,” write “Move hands to ~,” which makes your fingers more likely to start moving. Once written, don’t polish it—proceed immediately to the next step.

Step 2: Reset Mind and Body with Three Deep Breaths

After writing the restart note, breathe with inhale 4 counts, lightly hold 1, exhale 6 for three cycles. Plant your feet on the floor, gently lengthen your spine, inhale through your nose, and exhale slowly through your mouth. As you exhale, soften your shoulders and jaw to release tension.

- If three isn’t enough, you can go up to six.

- What matters is keeping the same rhythm every time. A steady tempo becomes a bodily cue that says, “We’re restarting now.”

Focusing on your breath lets you drop evaluation for a moment and return attention to action. If you miscount, just start over—it’s no problem. The key is having a pattern: “When I restart, I always take three breaths.”

Step 3: Slip Back into Flow with a Two‑Minute Warm‑Up

When the breathing ends, do a two‑minute warm‑up. The goal isn’t results—it’s to warm your hands and recall context. Starting with light tasks naturally brings the flow back.

- For writing: reorder headings, read the last three lines aloud, or fix obvious typos.

- For code: run a single test, align variable names, or review a checklist.

- For studying: read the problem conditions aloud, sketch the diagram, or copy one formula.

After two minutes, stop once and write a one‑sentence answer to “What came back in those two minutes?” Then move on to the main task you wrote in the restart note. If the flow still hasn’t returned in two minutes, rewrite the restart note and repeat the same steps.

My Personal Rules for Restarting Tasks

When I’m using the Flowtime Technique, I put on over‑ear headphones before I begin a task and start the radio or music. Then I start a timer linked to the task, and when I sense a stop signal, I take a break. Following the Flowtime Technique, I allocate 20% of work time to breaks, letting the break length be calculated automatically. I jot down the in‑progress task and purpose in Mac’s Stickies, then leave the desk for a quick bathroom or coffee break. When time passes and I return to the desk, I put the headphones on again, review the note, and write down how far I will progress on the next task—that’s my routine.

For headphones, I use noise‑cancelling models like Bose or Apple’s AirPods Pro to reduce noise and help me shift into a focused state.

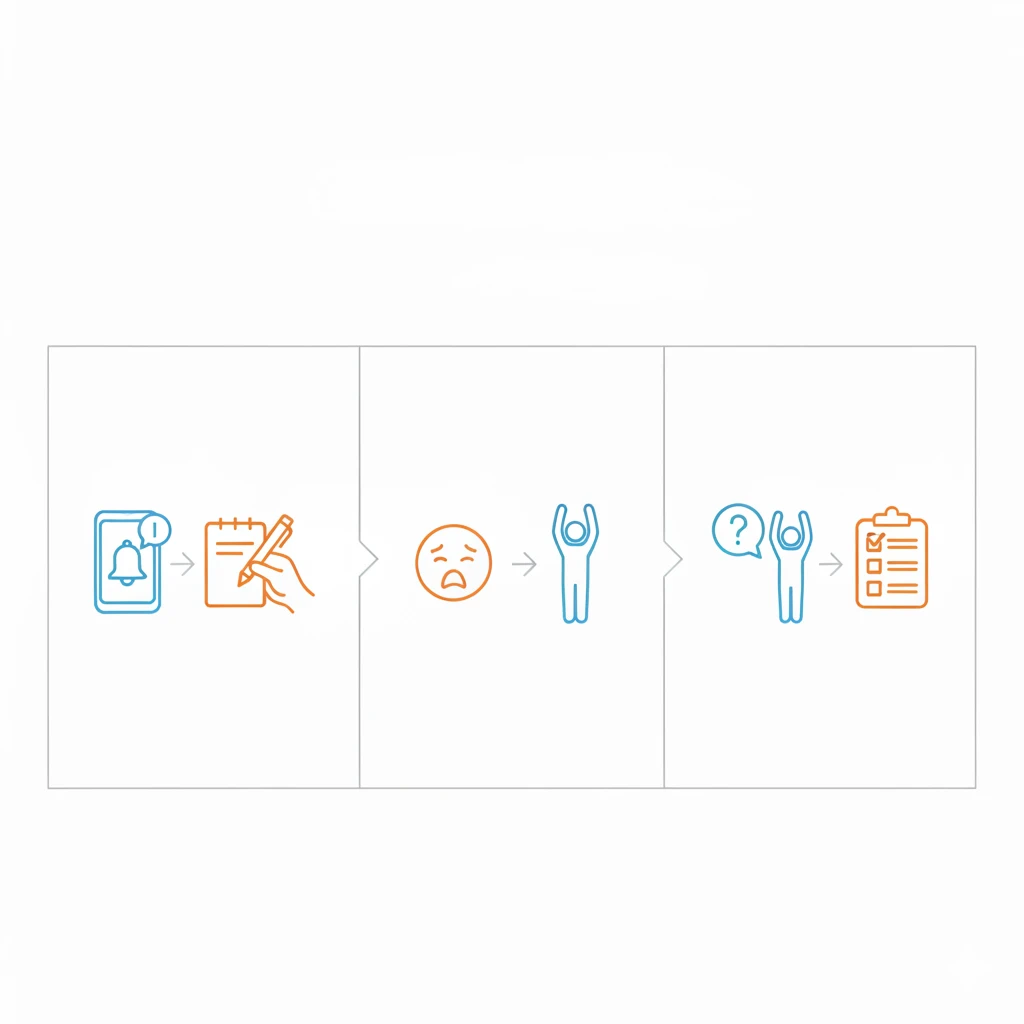

Tips by Reason for Interruption

Effective responses differ depending on the reason for the interruption. Think in three categories.

External reasons (notifications, being called away, etc.)

- Summarize the interrupting matter in a short note and list everything that must be done.

- Getting all your concerns onto the note frees up mental space.

State-related reasons (focus loss, sleepiness, etc.)

- If sleepy, stand up, move your body, splash your face—add stimulation.

- If it’s just boredom, restate the purpose of the work in one sentence and remind yourself “why.”

Process/system reasons (lack of planning, etc.)

- List required materials and files and make an ordered checklist.

- Before the restart note, decide “today’s entry point” in one sentence to avoid dithering.

Three Checks When You Still Can’t Get Back

If you still can’t move forward, review these three in order:

- Is the restart note too big (is it a small physical action, not the whole task)?

- Are you skipping the sequence of breathing and warm‑up?

- Did you put your anxiety or fuzziness into words before restarting?

If any one is missing, rebuild from there. In particular, #1 and #3 often become major causes of stalled hands.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q. How is this different from the Pomodoro Technique?

A. Pomodoro alternates focused work and breaks in fixed time blocks. The restart cues here are specialized for the moment you return from an interruption. Combining the two gives you both a set rhythm and restart that honors continuity.

Q. Is two minutes enough after a long interruption?

A. If more than half a day has passed, split it into three sets of two minutes. In the first two, read your previous note aloud; in the next two, write down five terms or numbers; in the last two, rewrite the restart note in more detail.

Q. How should we share this in a team?

A. Place a restart‑note template in a shared document and fill five items: object, action, deliverable, constraints, purpose. If you review it together before meetings, cross‑talk drops.

Q. Can this be used for studying or exam prep?

A. Yes. Speaking and copying are especially effective. Create restart notes bounded by count, such as “Speak two definitions aloud and copy them into the notebook,” to make returning easier.

Q. How long until it becomes a habit?

A. Repeat for about two weeks, aiming for ten times a day, and you’ll internalize “my hands move naturally after the breaths.” On days the sequence breaks, don’t give up—just start again from the top.

Summary: If You Align the Cues, You Can Return Anytime

Restarting a task is decided not by willpower but by cue design.

A label called the restart note, a bodily act of three breaths, and a brief two‑minute warm‑up. If you always chain these three in the same order, the flow returns naturally. Interruptions happen to everyone, but the way back can be practiced. Each time you sit down, align the small cues, and use the three breaths and two‑minute runway to get rolling again. With steady accumulation, restarting won’t scare you anymore.

For How to Stop Flowtime Technique, click here.

For the Guide to Choosing Tasks Suitable for Flowtime Technique, click here.

For the Overall Picture of Flowtime Technique, please go here.

If you have never started Flowtime Technique before, be sure to check out the Complete Guide to Flowtime Technique.

References

Why Is It So Hard to Do My Work? The Challenge of Attention Residue — Sophie Leroy (2009, Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes)

Implementation Intentions: Strong Effects of Simple Plans — Peter M. Gollwitzer (1999, American Psychologist)

How Breath-Control Can Change Your Life: A Systematic Review on Psychophysiological Correlates of Slow Breathing — Zaccaro et al. (2018, Frontiers in Human Neuroscience)

Encoding Specificity and Retrieval Processes in Episodic Memory — Tulving & Thomson (1973, Psychological Review)

Context-Dependent Memory in Two Natural Environments: On Land and Underwater — Godden & Baddeley (1975, British Journal of Psychology)

The Relation of Strength of Stimulus to Rapidity of Habit-Formation — Yerkes & Dodson (1908, Journal of Comparative Neurology and Psychology)

Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience — Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (1990, Harper & Row)

The Fresh Start Effect: Temporal Landmarks Motivate Aspirational Behavior — Dai, Milkman, Riis (2014, Management Science)

Über das Behalten von erledigten und unerledigten Handlungen (Zeigarnik, 1927) — The Zeigarnik Effect

Getting Things Done: The Art of Stress-Free Productivity — David Allen (2001)